I’M SO NOT INTO SPORTS: never have been, never thought I would be. But while experimenting with open-mindedness last spring, I began to wonder if I had a right to my indifference, given how little I know. Billions of people loved sports. Maybe before dismissing them I should learn what they were?

Welcome to Get Me Into Sports: conversations between people who know a lot about particular sports, and me. Future episodes will look at basketball, golf, MMA and so on. But first we’ll be hearing from the baseball fan I blame for all my problems.

My father grew up in New York City, in a family of traumatized ex-Dodger fans trying to come to terms with the Mets. Young enough to approach the city’s new team without invidiousness, Dad and his brother became super-fans. Dad’s loyalty to the Mets withstood his move to Vermont in his late 30s, and survived another decade before Red Sox Nation wore him down. My uncle ripped his shirt when he found out.

Through the summer of 2021, Dad humored my questions in his kitchen, his screen porch, his study. He typically wore a zip-up hoodie with comfortable gray sweatpants, and drank the right amount of coffee. I wore decorative leggings and drank too much. Later I edited the transcript for the usual reasons—concision, verve, clarity—and to make myself less annoying.

ALICE: How psyched are you that we’re doing this?

DAD: I’m delighted. I thought this day would never come.

ALICE: So you won’t mind if I start you off with a curveball hahaha.

DAD:

ALICE: True or false. You never taught me baseball to punish me for being a girl.

DAD: Completely false.

ALICE: I remind you that you’re under oath.

DAD: I bought you a bat, a T, and a glove, as you know. You did well on the T. When you couldn’t hit pitches, you threw a tantrum and stomped off.

ALICE: I did that with everything.

DAD: Yes.

ALICE: With piano, you were like, “Go upstairs, get the screams out, come back, and finish practicing.” With sports, it was just, “Here’s a cookie.”

DAD: I was choosing my battles.

ALICE: Your priorities for me were gendered, is all I’m saying. If I were a boy?

DAD: Let’s try a baseball question.

ALICE: 🤬 [Thumb-scrolls past three questions.] Your next baseball question is: “Everyone knows baseball is dull as f—k. How can you possibly find it so thrilling?”

DAD: I don’t.

ALICE: Excuse me?

DAD: A good basketball game is thrilling from start to finish. Same with football. Baseball doesn’t offer that kind of steady charge.

ALICE: You watch it for hours.

DAD: Not for thrills. Look. [His business partner] watches golf. I can’t handle that much sedation. Golf is for catatonics, football’s for adrenaline junkies. Some of us fall in between. We need to idle after work, but we’re not ready to let go of all the day’s tension. I’m going to sound like George Will.

ALICE: He’s a dork.

DAD: He’s nonetheless written well about baseball. He said something enjoyably pompous, once, about the game’s tempo. [Dad squints the way he does when he can’t remember something.] Never grow old.

ALICE: You’re not old!

DAD: Never say that to old people.

ALICE: Sorry.

DAD: Anyway, it was a simple enough point. If you can stand a music analogy—

ALICE: Elevator music?

DAD: I was going to say an adagio that threatens to accelerate more often than it does.

ALICE: That makes it sound gripping.

DAD: Gripping is right. More gripping than thrilling.

ALICE: Though when I watch a baseball game?

DAD: Do you watch? Or do you play with your phone and complain that the game you’re not watching is dull?

ALICE: I don’t say that about the football games I’m not watching.

DAD: With football, you cover your eyes and say, “Too many things happening!”

ALICE: [laughing] There are! And the players look like synchronized robots. How are you supposed to know what they’re going through when they hide their faces?

DAD: Their bodies are expressive, and you can impute emotion based on the result of each play. But I take your point. You’d prefer a sport that lets you read emotions off a player’s face. A sport like baseball.

ALICE: Or tennis.

DAD: Tennis isn’t a team sport.

ALICE: So?

DAD: Rooting for a team ties you to a region and the people who live there. Tennis players are rootless. Can you tell me where Roger Federer lives?

ALICE: Like the Ritz-Carlton.

DAD: [laughs] Switzerland. Which is also not a real place.

ALICE: You’re telling me you became a Red Sox fan, that you broke your brother’s heart and disgraced the family, just to tie yourself to New England?

DAD: Yes. And conversely, I stuck with the Mets too long out of ambivalence toward New England. I told myself this was a temporary stop for us, not our real home.

ALICE: You told me that, too.

DAD: Unlike piano lessons, that is something I regret.

ALICE: Since you raised the subject.

DAD: Let’s not.

ALICE: Just admit it’s weird how I walk past that thing every day without touching it.

DAD: I’d call that sad. But even if you never play again, I take solace in knowing you’ve internalized the structures and logic of piano music. You’re a better listener than you would have been. A better fan.

ALICE: I love where you’re heading with this.

DAD: There you go.

ALICE: Would you spell it out for people who can’t read your mind?

DAD: So I’ve always assumed there’s a valuable way to hear music that’s only accessible to practiced musicians. My assumption could be wrong.

ALICE: No, I think it’s right.

DAD: The same goes for baseball. I’m sure any fan can get a great deal out of watching a game. But it’s another thing to feel each play twitch in your arms and legs as it’s unfolding. Say I’m out at [our local school’s] field. While the pitcher takes the sign, the third baseman rocks back and forth to keep himself limber, and I limber up, too. When the pitcher sets, Third empties his mind to become one with the space between his glove and the batter. He may not have time to think before the ball reaches him. He reduces his mind into a reactive muscle. In the stands, I do the same.

ALICE: That sounds amazing.

DAD: It can be frustrating. Pro infielders always know where to position themselves, but the kids up here screw up. The other day, Third was playing the centerfielder too deep on his first at-bat. It’s always a good bet the centerfielder is the fastest runner on the team, and this guy looked the part. But Third wasn’t adjusting and I was worried he’d have to rush his throw. I was leaning forward, willing him to step in toward the plate.

ALICE: Sounds like it’s hopeless for me. I’ll never feel that about baseball.

DAD: We can drive out to [the school] right now. I can hit you some grounders.

ALICE: Ha very funny.

II. A HISTORY LESSON

ALICE: My next question [checks iPhone] is dumb.

DAD: Try me.

ALICE: “Why is baseball our national pastime?”

DAD: Most would say it lost that status to football, decades ago. But if you’re asking why baseball became preeminent in the 1870s and remained so for nearly a century, that’s not a dumb question.

ALICE: Phew.

DAD: How far did you get with Thorn?

ALICE: Thorn.

DAD: Did you open it?

ALICE:

DAD: So there’s this old chestnut about baseball, that it’s a pastoral game: its green fields hearken back to our agrarian roots, to villages where neighboring farmers met on the commons for clean Christian fun.

ALICE: That’s not true?

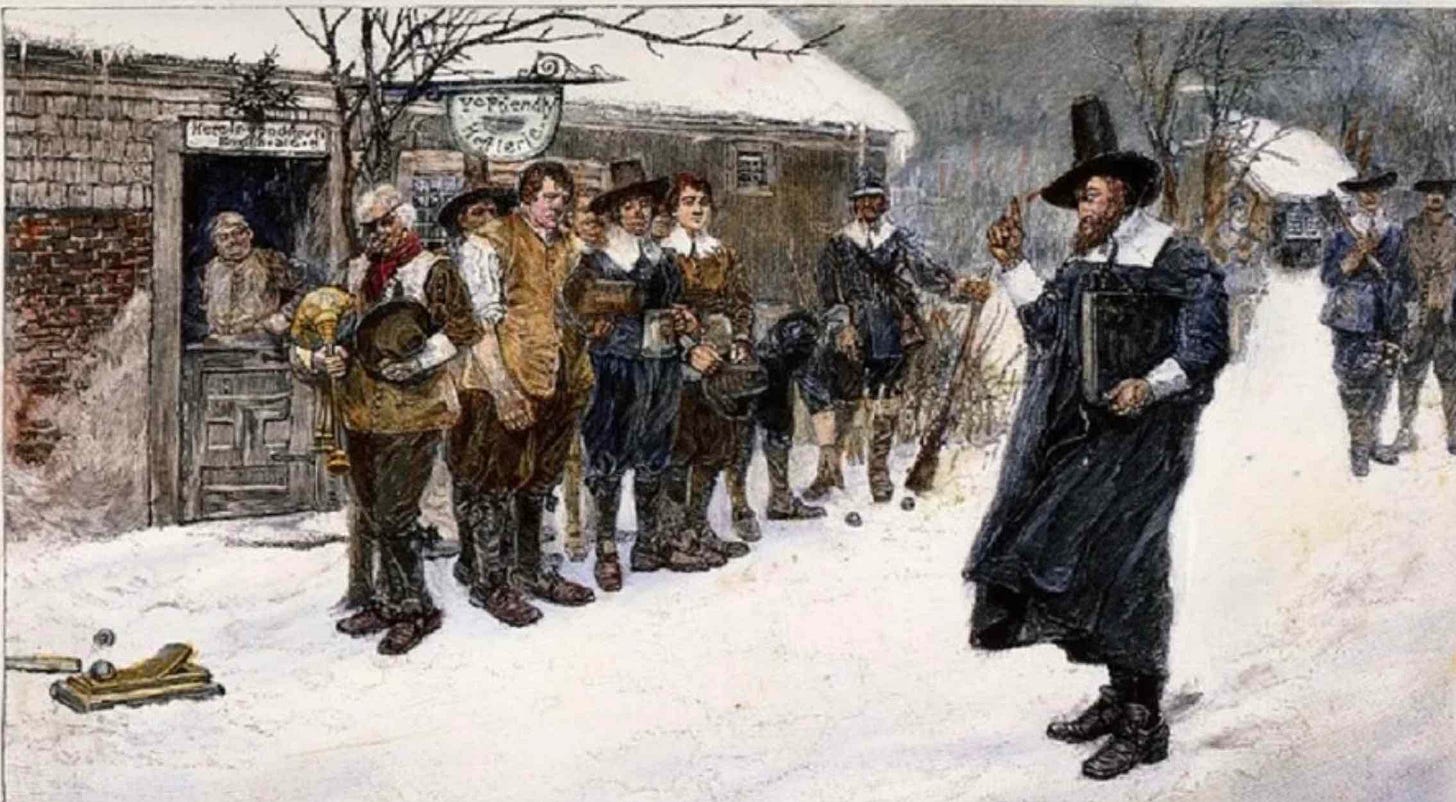

DAD: Not really, and I’ll explain why in a moment. But first, we need to get a few things straight. When the colonists first came over, they brought all sorts of stick-and-ball games from England. Some games had the equivalent of bases. Bradford mentions one in his journal, “stoole-ball.” This is right at the start, 1621. He had caught some of the new arrivals playing stoole-ball on Christmas.

ALICE: And jumped right in!

DAD: You’re correct he did not. He chewed them out and confiscated their ball.1

DAD: Later, in the mid-1700s, the English began to call one of this large family of games “base ball,” two words. But “base ball” wasn’t any closer to modern baseball than stool-ball, or other games from the era called stump-ball, round ball, cricket, wicket, and so on. Many of these shared a now-familiar action sequence. One person tossed a ball at a stationary object, say a stool. Another tried to knock the ball away with a stick. Successful knockers had the chance to run somewhere, while others chased after the ball.

In America, the earliest record of “base ball” is from 1791, in Pittsfield, Mass. The term showed up in the town board’s minutes. (It was actually Thorn who discovered the minutes.2 ) But again, there’s no reason to think Berkshires “base ball” was more germane to the current game than “round ball,” say. Same goes for the game Jane Austen called “baseball,” one word.

ALICE: Jane what?

DAD: She mentioned it, don’t ask me where. This is why baseball nerds like Jane Austen.3 My point is that a variety of ball games were popular here and in England into the early 1800s. And yes, the games were popular with farmers, simply because 90% of Americans lived on farms. So in that sense the game had a pastoral origin.

ALICE: However.

DAD: Go ahead.

ALICE: I just know it’s However Time.

DAD: It sure is. Because the game as we know it took root, took shape, became explosively popular in cities. The first organized leagues were in New York, Brooklyn, and Philadelphia, our largest, most industrialized cities. We call baseball teams “clubs” because the first teams grew out of men’s athletic clubs: an urban institution, and one that gathered strangers from all around, not just friendly neighbors on a commons. The “New York rules” that eventually dominated the game were first codified by a club called the Knickerbockers. They played the Gothams, the Empires, the Metropolitans, and, in case anyone missed the point, “the New Yorks.” That’s how bucolic.

ALICE: Hilarious.

DAD: Now, I don’t know how much of the pastoral innocence crap kids absorb these days. Anyone who’s seen the Ken Burns series has a more realistic view of early baseball than I had as a kid. But the myth lives on in other forms. There’s still a Puritanical expectation of virtuous conduct in baseball players that you don’t see in other sports, certainly not to the same degree. Middle-aged baseball fans with jobs and families, men and women who’ve experienced the real world, still fixate on the Black Sox. They can’t possibly be this naive, but they speak as if baseball lost its virginity in 1919, and barely survived God’s wrath in the years after. I’ve strayed from your question.

ALICE: No this is good. You’re telling me that being a great game everyone loved wasn’t enough to make baseball the “national pastime.” They needed purity.

DAD: Yes.

ALICE: So when did the game lose its virginity?

DAD: The answer shouldn’t surprise anyone because it’s always the answer. Corruption was baked in from the start. The leagues were technically amateur until the 1870s. This meant that while owners of the parks charged admission, they didn't formally pay the players. But to field the best players you had to give them some incentive to show up. Most of the fans were city workingmen new to the country, mainly Irish and Germans. They gambled on cockfights, elections, raindrops on a window. The gamblers cut the players in, with predictable results.

ALICE: And everyone knew this?

DAD: Absolutely. I’m not saying gambling had no downsides. Along with the obvious, it put a ceiling on the game’s respectability. Prigs in the New York Times deplored baseball and called for “reform.” But the Gilded Age by and large saw gambling as a common vice, not a Satanic temptation with the power to destroy an entire sport. One of the owners’ arguments for professionalization in the 1870s—their public argument—was that salaries would reduce the demand for bribes. Of course their real motive was profit, and once the owners had a quasi-monopoly they underpaid their players, who kept taking bribes. We’re talking about those burly guys with the funny mustaches.

ALICE: They’re adorable.

DAD: These adorable men weren’t in a position to turn down cash. The White Sox owner, Charles Comiskey, was one of the stingiest. He had no illusions about his players, though in 1919 he pretended to be scandalized along with the press.

ALICE: We can move on, but just, when did the phrase “national pastime” show up? I’m guessing Reconstruction?

DAD: It would have to be sooner. There’s a famous Currier and Ives of Lincoln with a bat towering over Douglas and Breckenridge.

DAD: I see now it says “national game,” not “pastime.” And Bell is there, too. This is why you shouldn’t grow old.4 Suffice to say baseball was already popular in the 1840s and became a national craze in the 1850s, supplanting cricket. From the captions, you can see how far the game had come culturally, even before the War. A mass audience knew all this slang.

ALICE: Douglas saying “short stop” is heightest.

DAD: Little Stephen. Five foot four, and Vermont’s own.

ALICE: For real?

DAD: He grew up in Rutland.5

ALICE: That’s so hard to imagine. Politically, I mean.

DAD: He hated Vermont. He was one of those. Impatient for a law career and the state bar wasn’t accommodating. He said he hated the Green Mountains for blocking his view.

ALICE: What a jerk!

DAD: He was describing the East and its limited horizons, drinking the frontier Kool-Aid. But I wouldn’t be surprised if he talked himself into hating actual mountains. Can you stand some more about cricket?

ALICE: Yes, please.

DAD: Cricket was still very popular throughout the Civil War. It was always less of a workingman’s game than baseball, but never exactly posh until the 1880s. At that point, cricket versus baseball became a culture war issue. Olmsted wouldn’t allow baseball in Central Park, only cricket. He didn’t want the Irish invading his masterpiece with their drinking, fighting, and gambling. The Times weighed in, pro-cricket of course, and boosters took advantage. They marketed baseball as a game for manly Americans, the guys who fought “Indians.” Whereas cricket was for girly-men from England, or Princeton. It had always been an Ivy League sport. By the First World War, that’s all it was. The Newport crowd sent their kids over to marry English aristocrats, and cricket fit in.

ALICE: It’s weird I can’t think of a cricket scene in Henry James.

DAD: You’d know better but I never thought of him as a sports guy. Did anyone ever see him run?

ALICE: He walked a lot in Italy and France. Later, he rode a bike because his doctor made him.

DAD: What an expression.

ALICE: I think he would have liked me.

III. THE RULES

ALICE: So with baseball, I do sort of know the rules. The main ones.

DAD: Sure.

ALICE: They just seem kind of arbitrary.

DAD: Which do?

ALICE: Like the runners. Why can’t two runners stand on the same base? And why can’t a runner catch a ball and throw it into the audience? Why is everything foul?

DAD: Well, if you’d read the immortal Thorn, you’d know he carries a torch for the 1850s Massachusetts Game, which had no foul territory. Runners in that version could also interfere with the fielders, and could flee to the outfield to evade a tag. To counteract that advantage, fielders were able to get runners out by throwing directly at them, “plugging” them with the ball.

ALICE: That sounds fun.

DAD: Thorn would agree. But he would not agree with you that changes to the rules since have been arbitrary. If you want an example of an arbitrary rule-change: running the bases counter-clockwise. Runners ran clockwise in an earlier iteration. Each direction slightly advantages righty or lefty batters, but there’s no fundamental difference. This is not something you can say about most of the game’s evolution, which has a logic.

ALICE: What’s the logic? Be as complicated as possible?

DAD: The rules evolved to make the game more itself.

ALICE: That sounds tautological.

DAD: I’d call it teleological. Each sport has a different ideal balance between offense and defense. Basketball’s ideal balance makes it easy for the offense to score. Soccer’s the opposite; the offense is so handicapped, they run like lunatics freed from an asylum after a goal. Baseball is somewhere between. The median starting player gets on base about a third of time. If he got on half the time, getting on base would be an expectation, not an accomplishment worth cheering. If he got on a quarter, the game would be dull.

ALICE: Even for you.

DAD: The rules change over time to restore this ideal balance between offense and defense whenever it seems in danger. Pitchers used to “pitch” in the original sense, throwing underhand, as with horseshoes. After batters started crushing the ball in the 1880s, the leagues allowed overhand pitches to make batting harder. In the 1910s, hitting became too hard, so they banned spitballs. In 1969, they lowered the pitcher’s mound to help hitters again. Now they’re talking about moving the mound farther from the plate, which is so insane it won’t happen but it’s meant to address a recent imbalance that favors pitchers, and makes the game dull.

ALICE: You’ve convinced me. The rules aren’t arbitrary!

IV. THE GAME ITSELF

DAD: What’s next?

ALICE: I still want to like, see what I’m not seeing.

DAD: You need to watch a game.

ALICE: A whole one?!

DAD: Let’s start with an inning.

We watched two at-bats of an old Red Sox game. Before the first pitch, the catcher flashed signs in front of his man parts and I paused the video.

ALICE: People hate the Houston Astros because they stole signs, right?

DAD: The objection was that they used technology to steal signs, and communicate them to the hitter.

ALICE: So why do signs at all? Why doesn’t the pitcher just throw whatever?

DAD: Because the catcher needs to be on the same page with him.

ALICE: He can’t just, like, catch it?

DAD: You need to understand that pitches aren’t ordinary throws. Picture a third-baseman throwing to first. He has a large target. Anywhere the first-baseman can reach without stepping off the base is fine. Also, infielders always try to throw straight, to get the ball there as quickly as possible, and to make catching it easy.

Pitches aren’t like that. They often move in strange ways to fool the batter. Without an agreed-upon pitch, they’d fool the catcher as well.

The pitcher took the sign and stared at the batter ferociously. I paused the video again.

ALICE: What’s with the stink eye?

DAD: Pitchers aren’t ordinary throwers. They work the edges of a small target, a matter of inches in or out. To do that consistently takes extraordinary concentration and attention to detail.

ALICE: And now the rigmarole.

DAD: The windup.

ALICE: Yeah.

DAD: Can you picture a cricket bowler?

I can’t, so we watch a cricket bowler on YouTube.

See how he takes a running start before releasing the ball? The run lets him gather linear force to transmit to the ball. But a baseball pitcher can’t run to the mound. He needs to capture more of his body’s rotational potential and turn that into linear force. Let’s watch the windup again.

We do.

First, the pitcher coils his body, creating tension. His center of gravity stays over his back hip until the last moment, when the weight-shift forward leads a rapid uncoiling. As a student of mechanics you’ll know why he extends his arm.

ALICE: Leverage!

DAD: His arm is a third-class lever.

ALICE: The fulcrum’s his big ol’ butt.

DAD: Meanwhile his grip on the ball and his wrist motion, or lack of it, influence the ball’s spin, adding whatever curve or “break” the pitch calls for.

ALICE: I love that pitchers know physics.

DAD: Intuitively, they do. The trainers are the ones who really study it. They have labs now where pitchers throw with sensors on their body. Trainers analyze the data for any inefficiency in their motions.

ALICE: Seems unfair.

DAD: It would be if batters didn’t do the same thing with their swings.

ALICE: So everyone’s a robot?

DAD: They’re precisely not robots, though technology helps them train.

ALICE: Still seems kind of inhuman.

DAD: In that case, let’s talk about the mental game. The confrontation between the pitcher and hitter is ultimately a physical contest but there’s a large mental component that precedes each pitch. At-bats have been likened to duels, or games like chess. The at-bat begins not with anything physical but with a series of decisions made by the catcher. His first decision is whether to have the pitcher throw within or without the strike zone. Obviously any pitch in the zone is more apt to strike the batter out if he fails to swing, but it’s also more dangerous to the fielding team. The batter can more easily get the meat of his bat on a ball in the zone.

Next, the catcher decides on a high or low pitch, closer or further from the batter, fast or very fast, and finally the break. Varying these decisions keeps the batter off his stride.

ALICE: So catchers are basically geniuses.

DAD: It’s not a coincidence so many of them go on to coach. But to your point, the catchers and pitchers also benefit from computerized data analysis. Before the game, they review tendencies in the hitter apparent from every pitch ever thrown at them They’re looking for his strong and weak spots. Of course, a pro’s weak spot can’t be too weak or everyone would throw there and he’d flop out of the majors.

Other big factors the catcher weighs before selecting a pitch are situational. Number of outs, baserunners, inning, batter on deck. Above all, the ratio of balls and strikes.

ALICE: “The count.”

DAD: Right. So let me ask you. How would a count of three balls and one strike affect the pitcher?

ALICE: He’s bummed.

DAD: Why?

ALICE: He doesn’t want to do a base on balls.

DAD: And how can he avoid that?

ALICE: Pitch in the zone?

DAD: Which the batter…

ALICE: Riiight. I got you. It’s some deep game theory.

DAD: Now consider it from the batter’s perspective. Say the batter has an unfavorable count. With no balls and two strikes against him, he’s under enormous pressure to swing. Laying the bat on the ball is infinitely better than taking a called strike three. But the pitcher knows this, and will prey on the batter’s anxiety. He’ll “waste a pitch,” throwing outside the zone to induce a low-probability swing.

ALICE: I know this is a dumb question but why don’t hitters just swing at strikes and not at balls?

DAD: You need to understand that batting’s an approximate skill. When the pitcher succeeds at working the edges of the zone, even the best eyes can’t reliably distinguish a strike from a ball. The batter has only tenths of a second to commit to a swing. And umpires make mistakes, too. So that split-second decision is influenced by whatever inclination the batter brings to each pitch. And that inclination reflects specific counts, which lead to different odds of the pitch arriving in the zone. On 3 and 1 counts, pitches hit the zone 70% of the time. That’s versus 50% for average pitches, or 35% when the pitcher has a big advantage.

ALICE: Most Americans can’t name the Chief Justice, but you’re telling me they know this?

DAD: Americans care more about sports than politics. You and your friends are odd.

ALICE: This is getting dark.

V. NOSTALGIA

DAD: I want to add something about the power of the pastoral innocence myth. Outside of baseball, I was as cynical and disillusioned as any teenager. But when I stepped onto a field, when my cleats sunk into the grass, or dirt if that’s all there was, it felt like entering an exalted realm.

ALICE: Exalted how?

DAD: A place of social harmony and justice. Effort and talent rewarded. Sportsmanship a sacred code. Events in a predictable order, with all the challenges clear. Baseball offered a contest that was uncorrupted and made perfect sense.

ALICE: You sound like a gamer.

DAD: How’s that?

ALICE: This is the stereotype, anyway. Guys who play a lot of video games can’t handle the messiness of real life. They need life reduced to a bunch of heroic contests with clear rules. Virtue triumphs, like in comics.

DAD: I don’t know what to do with your contemptuous tone here, but you’re onto something in my case. A deep part of me has always preferred clear and simple rules. You were different, and that’s one reason I didn’t insist on your learning sports.

ALICE: See, this is all I wanted from you.

DAD: OK

ALICE: And also that these differences are gendered, which—I don’t know how you can deny it.

DAD: I don’t know that parents can do much about the inclinations you view as socially “gendered.” They are probably innate.

ALICE: The video-game gene.

DAD: It’s easier to mock that idea than defend an alternative. But let’s stick with baseball?

ALICE: For the record, I always liked it when we went to games. I liked being where you were so happy, with so many other happy people.

DAD: Ballparks are sublime. Even now, with seven-dollar hot dogs and twelve-dollar beers, with the cheesy sound effects. Somewhere in this house there’s a neat book you’ll never read about ballparks, called Green Cathedrals. The title’s not much of a stretch.

DAD: [Checking out a photo on my phone] What a terrific shot. Do we know who took it?

ALICE: The internet?

DAD: They had better seats than we did. Your readers may want to know that we’re discussing a photo of Shea Stadium. The weather’s perfect for baseball: warm but dry, with a breeze blowing out to left. The upper deck’s packed because the Reds are in town. This was the Big Red Machine, the best team of the 1970s. You know it’s the Reds and not the Cardinals from the two stripes around their waist. And look at that burly guy on-deck, with a “4” on his back, his black hair falling out of his helmet. That’s got to be Pete Rose, number 14, speaking of gamblers. The all-time hit leader, and he’s still kept out of the Hall of Fame by the Jesuits. Ken Burns said Rose should only be admitted after he dies, because he “doesn’t deserve to know he’s in the Hall.”

ALICE: Ew.

DAD: That’s the moderate view. But I’d rather talk about this terrific photo, which is from ’77 or ’78. Would you like to learn how I know that?

ALICE: I would.

DAD: We start with the scoreboard ads. Through 1973, the Mets’ beer sponsor was Rheingold, with its “ten-minute head.”

ALICE: It’s what?

DAD: Budweiser came in for the 80s. So just from the Schaefer sign out there, we can narrow the years down to six, 1974-79. Now we do soft drinks.

ALICE: I love this.

DAD: RC Cola was the classic Mets sponsor. RC was up in ’69 when the Mets won the Series. By ’73, when the Mets lost the Series, you had Getty gas: not a soft drink for most of us. For ’75 and ’76 you had Dairylea milk. Milk was a stand-alone beverage in those days. Adults drank it with hot dogs.

ALICE: I can’t even.

DAD: Now the Coca-Cola sign which you see in this photo replaced Dairylea in 1977. So we’ve cut the possible years down to ’77, ’78, ’79. Except you can cross off ’79 because Pete Rose had left for the Phillies.

ALICE: There’s no way every fan knows this. You’re a savant.

DAD: Last thing. If it’s ’78—and that’s my hunch—it was likely during Rose’s 44-game hitting streak. Three or maybe four of those games were at Shea.

ALICE: OK, Rain Man.

DAD: Thirty-five years ago, that might have been an accurate insult. Then I could have told you the height, weight, and career home runs and batting averages of both rosters. But any Mets fan my age would know the scoreboard ads. God fans memorize Bible passages. Baseball fans memorize trivia.

ALICE: When you go to a ballpark now, do you still feel exalted?

DAD: I don’t feel anything the way I used to.

ALICE: Let the record show: Dad’s still mooning over the photo of Shea.

VI. LAST BIT

DAD: Before we wrap up, I want to show you the greatest third-baseman of all time. Nolan Arenado. It’s a privilege to watch this man in his prime.

Dad makes me watch a ten minute highlight video of Nolan Arenado making truly insane catches and throws. Dad’s bummed he can’t find footage of the guy between pitches (staying limber, becoming one, etc) but his plays are legit thrilling. Arenado throws while sitting or leaping or running the wrong way, and the announcers shout things like, “Cut it out!”; “Stop it!”; “Are you KIDDING me?”

DAD: Not a bad looking guy.

ALICE: Not at all.

DAD: Is he your new favorite?

ALICE: I’m going to say “yes” because I can’t think of anyone else.

DAD: You used to love Pedro Martinez.

ALICE: You loved Pedro, and I was a monkey who thought whatever you did was best.

DAD: This is why you have good taste.

ALICE: 🥰

DAD: This has been a lot of fun. I don’t want it to end.

ALICE: We could go to the school and play catch. Just kidding.

DAD: Why kidding?

ALICE: It’s raining.

DAD: I’d call this a drizzle.

ALICE: I don’t want to change into sneakers.

DAD: Your hikers are fine.

ALICE: It would make a cute ending, I have to admit.

DAD: I believe you owe it to your subscribers to play catch with your old man.

ALICE: You’re right. I do.

Bradford’s 1620 Mayflower cohort was doctrinally stricter, and more scrupulous, than the newcomers who’d stepped off the Fortune. In Plymouth, Christmas was an ordinary workday because the Bible doesn’t sanction its celebration.

Yet on Christmas 1621, some of the Fortunites told Bradford that their consciences didn’t allow them to work on Christmas. The governor opted not to make a whole thing of their “error,” and left them alone. He expected them to spend the day indoors, in prayer and contemplation. Imagine his vibe when he found them frolicking in the streets at noon playing “stoole-ball.”

More from Dad: “The town wanted to protect the windows of its meeting hall from stray projectiles. They outlawed the playing of seven window-breaking games within range of the hall. One of the few things you can fault Thorn with is that he sometimes recounts this story in a way that lets a reader think “base ball” was a special target of the ordinance. It was not. Thorn also speculates that its place on the list meant “base ball” would have been played all over the Berkshires. It seems more likely to me a Pittsfield lawyer was good at his job and included every ball game anyone could think of.”

Northanger Abbey, from the opening description of its heroine, Catherine Morland: “It was not very wonderful that Catherine, who had nothing heroic about her, should prefer cricket, baseball, riding on horseback, and running about the country at the age of 14, to books.”

Less well known is Austen’s reference in Persuasion to an “umpire.” Anne Elliot “staid at home, under the mixed plea of a headache of her own, and some return of indisposition in little Charles. She had thought only of avoiding Captain Wentworth; but an escape from being appealed to as umpire was now added to the advantages of a quiet evening.”

Old Dad was half right. “National pastime” only became common parlance after the Civil War, but it does appear before, first in an 1856 New York Mercury.

Stephen Douglas was born and raised in Rutland County, but more precisely in the village of Brandon, 15 miles north of the village (now city) of Rutland.

This was delightful, but I have a simpler explanation for why baseball was the pastime for a hundred years:

1. It was played at a MUCH FASTER pace than it is today

2. Because there are a small number of discrete, easily visualizable events, and has a daily rhythm, it is the best sport to follow in the newspaper.

3. For similar reasons, it is arguably the best sport on the radio.

Put simply, television wounded baseball and the modern style of play is going to kill it.

I played a ton of baseball as a kid (from age 4 to age 15) because my dad loved baseball. He'd played as a kid. Back when, as he would describe it, "there was nothing else to do". He also had his favorite team (White Socks), and would tell me stories about players long since dead or retired. I still follow my local teams (Nats and Orioles), but I lack his passion for the game. I think the excitement of waking up on a warm summer day in Illinois and going out to play baseball with all of your friends from school. Back when there really was nothing else to do, and the warm months beckoned for you to be outside. I missed a lot of that. For me, there was so much to do, and so little time I could devote to each individual thing. It's interesting. I appreciate baseball. I'll go to games a few times a year, try to watch most of the games my teams play, and religiously watch the world series. But the love for it isn't there like it was for my dad.

Also, this interview is real or you're a very good writer. Virgil Texas and Matt Yglesias do not write this well, nor can I imagine their fathers being into baseball... maybe Yglesias. You are not them.